Documentation of residency from 22 November, 2022 to 30 April, 2023.

Centre for Projection Art’s Artist-In-Residence program pairs an artist who is emerging and experimenting with projection through their contemporary art practice, with an artist mentor for four months. This provides opportunities for artists to develop their creative skills in the projection field, develop new artwork for public presentation, collaborate and expand their professional networks.

centreforprojectionart.com.au/residencies

¶

What do you wish to achieve or learn throughout your residency?

I wish to become projection literate in order to expand my film and digital work beyond the boundaries of screens and into activations in three-dimensional space. Extending upon my experience and interest in technologies, I am looking to construct immersive and interactive experiences that promote juxtaposition and exchange between virtual worlds and physical environments. In particular I will focus on developing a forthcoming exhibition that is an unconventional hybrid of documentary, narrative and publication. I also hope to find ways to integrate projected imagery into the traditionally non-digital facets of my practice including wearables and objects.

¶

Induction and a site tour of the Mission to Seafarers was held on 29 November, 2022.

¶

A projector was collected from Centre for Projection Art after an induction to Collingwood Yards on 14 December, 2022. Playing with the projector in the studio commenced the following week.

¶

Some research and critical thinkinging about the form of publications occured across December and January.

Goals:

- question the legitimacy of, and offer alternatives to, the printed word

- critically dissect the structure and function of publications

- consider applications that incorporate installation, moving image and sound

Aspects to build on:

- ‘material space for critical self-reflection and exchange’

- ‘imbue [the publication] with a certain character’

- ‘compel a [viewer]’

- ‘critical analysis of the content’

- prioritise ‘the quality of the book’s constituent parts’

- ‘convey a narrative’

- comfortable for extended viewing

Aspects to re-consider:

- ‘succinctly communicate’ content

- implied ‘objectivity’

- ‘perfected’ conventions

- standard physical, visual, typographic and synoptical form

- one dimensional (and directional) ‘structure and sequence’

- authoritarian presentation and voice

- solitary use

- static, permanent, enduring

- hierarchical layout

- application of pigment (dark markings on a lighter surface)

- western histories, contexts and frameworks

What a book generally consists of:

- a container: front cover, back cover, spine, binding

- kinds of pages: title page, frontispiece, colophon, acknowledgements, foreword, contents, epigraph, introduction, chapters, appendix, notes, glossary, bibliography, index

- interior page content: headings, paragraphs, notes, captions, images, margins, columns, gutters, page numbers, index

What a book generally does not consist of:

- paratexts

- moving image

- sound

Book alternatives:

- songs

- oral literature

- objects and wearables

- inscriptions on objects and environments

- scrolls

- tablets

- electronic media

- people

Other formats to borrow from:

- film: title sequences that convey information while enhancing mood and providing transitions, sound enhances visuals

- music: layers of simultaneous sounds, harmony between different elements, collectively created

- visual art: (subjective) frame serving as a boundary of a work, critical exploration, indirect communication

- architecture: consideration of space, surrounding presence, collective viewing, collective memory, formal and informal use

- nature: ecologies, cycles, evolving forms, biotic symbioses (mutualism, parasitism, and commensalism)

¶

Late January and early February were used to play with a projector in the studio and thinking about works that could be shown at the Mission to Seafarers.

¶

The projection masterclass lead by Yandell Walton took place 11–13 January at the Mission to Seafarers.

¶

Masterclass day 1 consisted of an introduction to the different applications and considerations when using projection, as well as examples of artists that use projection.

Exploring projection in art:

- large scale projection

- building mapping

- participatory / interactive (e.g. shadow of body, doesn’t have to be technology)

- site responsive (e.g. connected conceptually or to features of site)

- object mapping (e.g. bring in or work with what’s there)

- installation (e.g. part of installation with other materials, multiple channels or projected elements within a space)

Site considerations:

- ambient light (e.g. sunlight that changes, light from other artworks, internal lights, street lights)

- colour of the surface being projected onto (the darker the background the darker the blacks but the brighter the projector needs to be, lighter surface has bright image but light blacks)

- size of image (smaller you go the brighter the image will be)

- projector brightness (ambient light and size of image used to determine what projector brightness is needed, measured in lumens)

- artwork colour and contrast

- artwork shape and form (artworks that use negative space will pop)

- power sources

- safety (e.g. ratchet straps, putting projector out of sight and reach)

Examples of artists:

- Team Lab (working with features of building in subtle way, highlighting elements, spectacle, technical difficulty)

- Club Ate (large scale building mapping with artistic integrity, ‘In Muva We Trust’ building mapping that is not cheesy, connects well to architecture)

- Isaac Julien (projecting onto screens installed in space, pivoted to create ‘portals’ into other spaces)

- Pipilotti Rist (installation with projection mapping onto specific objects and different surfaces within a space, immersive in different way by asking viewer to lie down to experience work, utilising shape of room)

- Maree Clarke (‘Born of the Land’, traditional aspect ratio but bringing in other, three dimensional elements into installation that cast their own shadows)

- Nota Bene (‘In Order to Control’,interactive typographic work that used a sensor projecting words inside viewer silhouette)

- Diana Thater (multichannel, combines sculpture and projection)

- Heather Phillipson (installation artist that uses multichannel and found elements)

- Nam June Paik (layering of projections, sculptural projector framework)

- Wonjun Jeong (projections onto fabric in mid air)

- Jenny Holzer (typography distorted by surfaces)

- Sab D’Souza (use of image and text really strong, frame references media but text pushes outside of frame)

¶

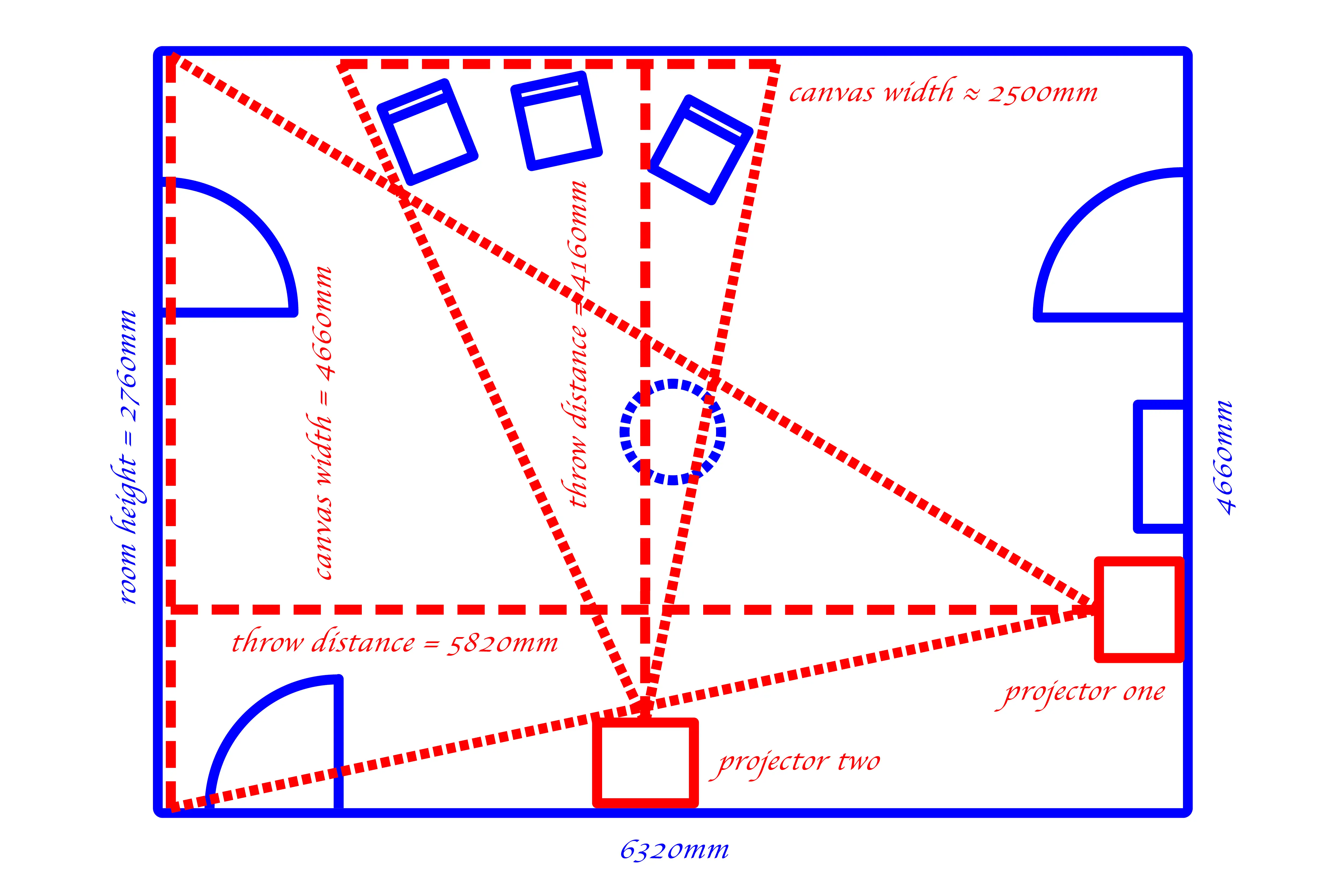

Masterclass day 2 focused on the technical aspects of projection.

Specifications:

- resolution

- brightness

- lens throw ration (e.g. standard or short throw, determines how big image will be)

- contrast ratio

- on off axis

Getting started:

- projector specification and features will determine the image size and placement

- look up projector model

- https://www.projectorcentral.com/projection-calculator-pro.cfm (use for consistent format between models, throw distance calculator)

- Epsons are recommended (in terms of colours, brightness, contrast level)

- projectors are either LCD or DLP (light moves through in a different way, loose lumens in process of light getting out, DLP less light than LCD, if using DLP might need more lumens)

Resolution:

- e.g. 4K 3840 x 2160, 1200p 1920 x 1200 (WUXGA), 1080p 1920 x 1080 (HD 1080), 800p 800 x 1280 (WXGA), 720p 720 x 1280 (HD 720)

- describes how clear a projected image will be based on how many pixels can be displayed on a given space

- one 4K player could be used in place of multiple lower resolution projectors

- BrightSign media player recommended for 4K

Throw Ratio:

- tells us what image size we can project from a certain distance away

- the smaller the throw ratio, the larger the image a projector will produce at a shorter throw distance

- image width x lens throw ration = throw distance

- take throw distance from the top of the lens and take into consideration depth of projector

- short throw lenses usually considered under 1:1

Projector Offsets:

- the offset measures the position of the image relative to the centreline of the lens

- in a projector with a 0% offset, the centre of the image lines up perfectly with the centre of the lens, assuming that the projector is pointed straight at the screen

Set Up:

- reset settings

- installation (e.g. front rear ceiling)

- focus, lens shift, zoom

- keystone, corner pin

- yes to calibration unless setup already

- reset all settings through menu

- if portrait need to mount in way that allows air flow

- cover all surfaces you want to project onto without going too far over edges

- make sure projector is secure and nothing can move either the object you are projecting onto or the projector

- note resolution from model (important to match the resolution)

Mapping and Masking:

- masking is described as masking out a shape with black so the content fits a certain designated area

- mapping is described as a pre-distorting content to fit a 3D shape so the content is not distorted

After Effects:

- extend desktop (extended display in system preferences)

- connect your projector as an output display showing you exactly what your artwork will look like in real time whilst editing

- when creating a composition be mindful of projector frame rate

¶

Day 3 of the masterclass consisted of installation proposals, as well as beginning mapping and the set up of projectors.

¶

Residents and the invited artists had self-led access to the space 16, 18–19 January to continue installation.

¶

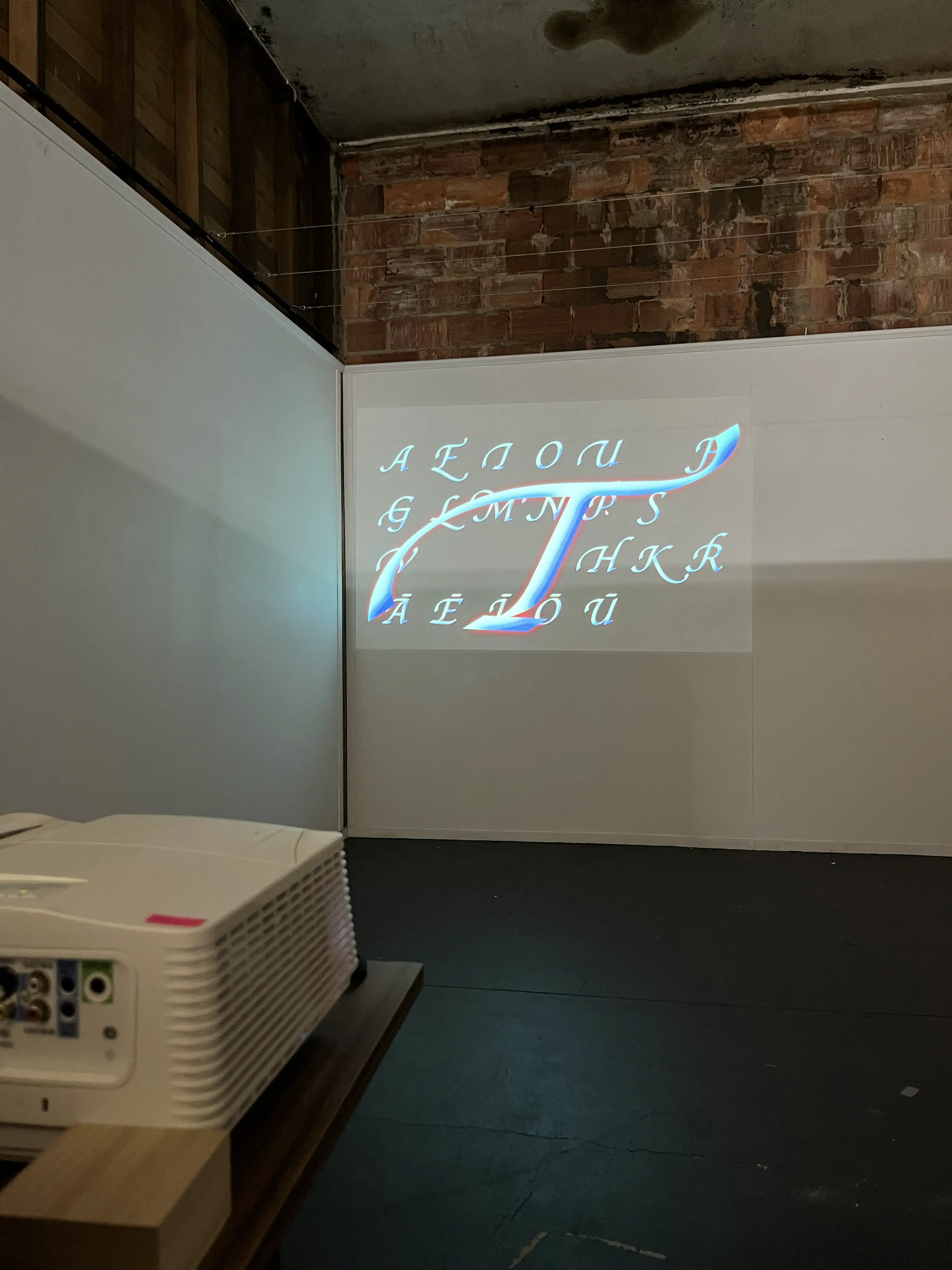

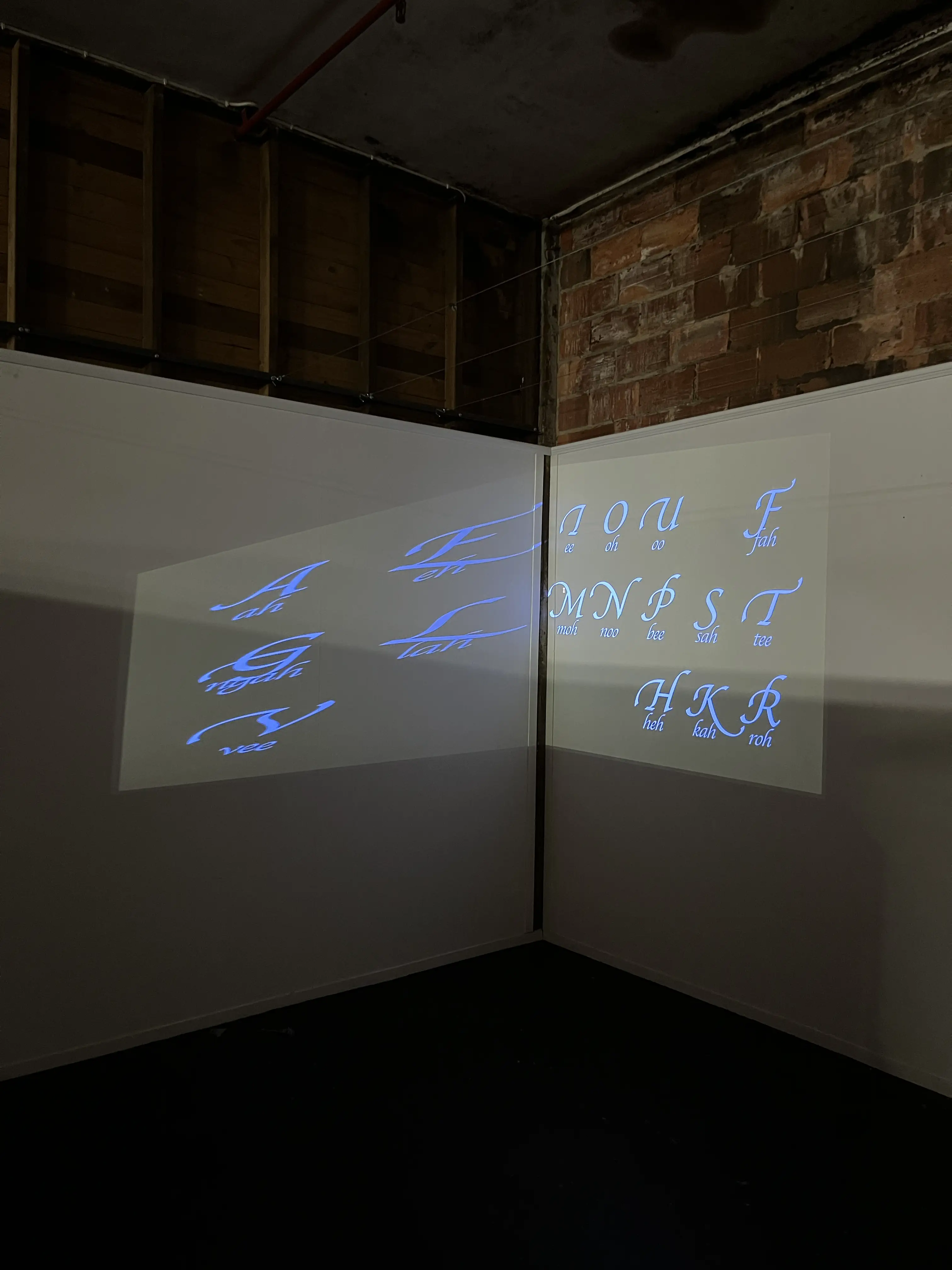

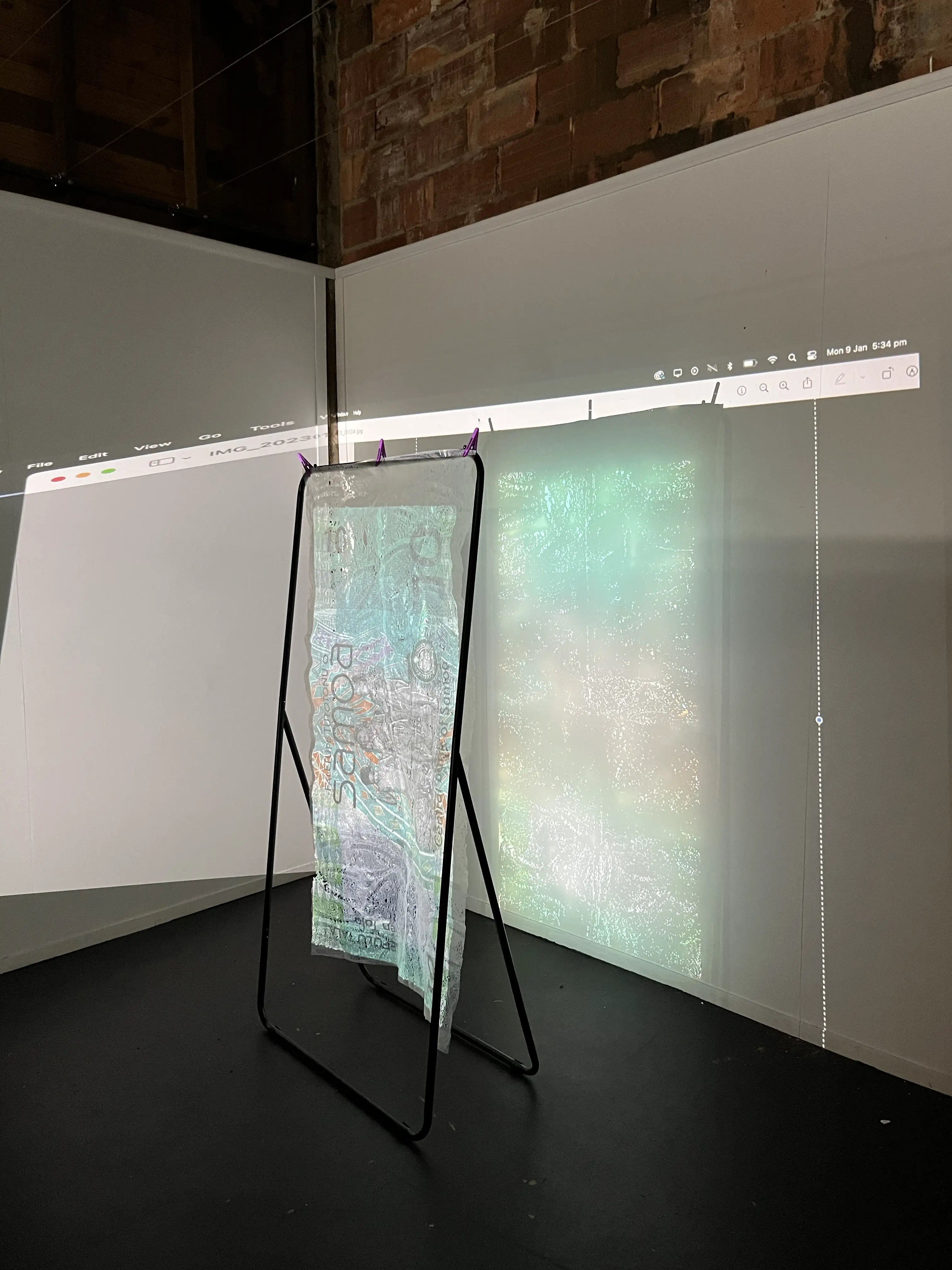

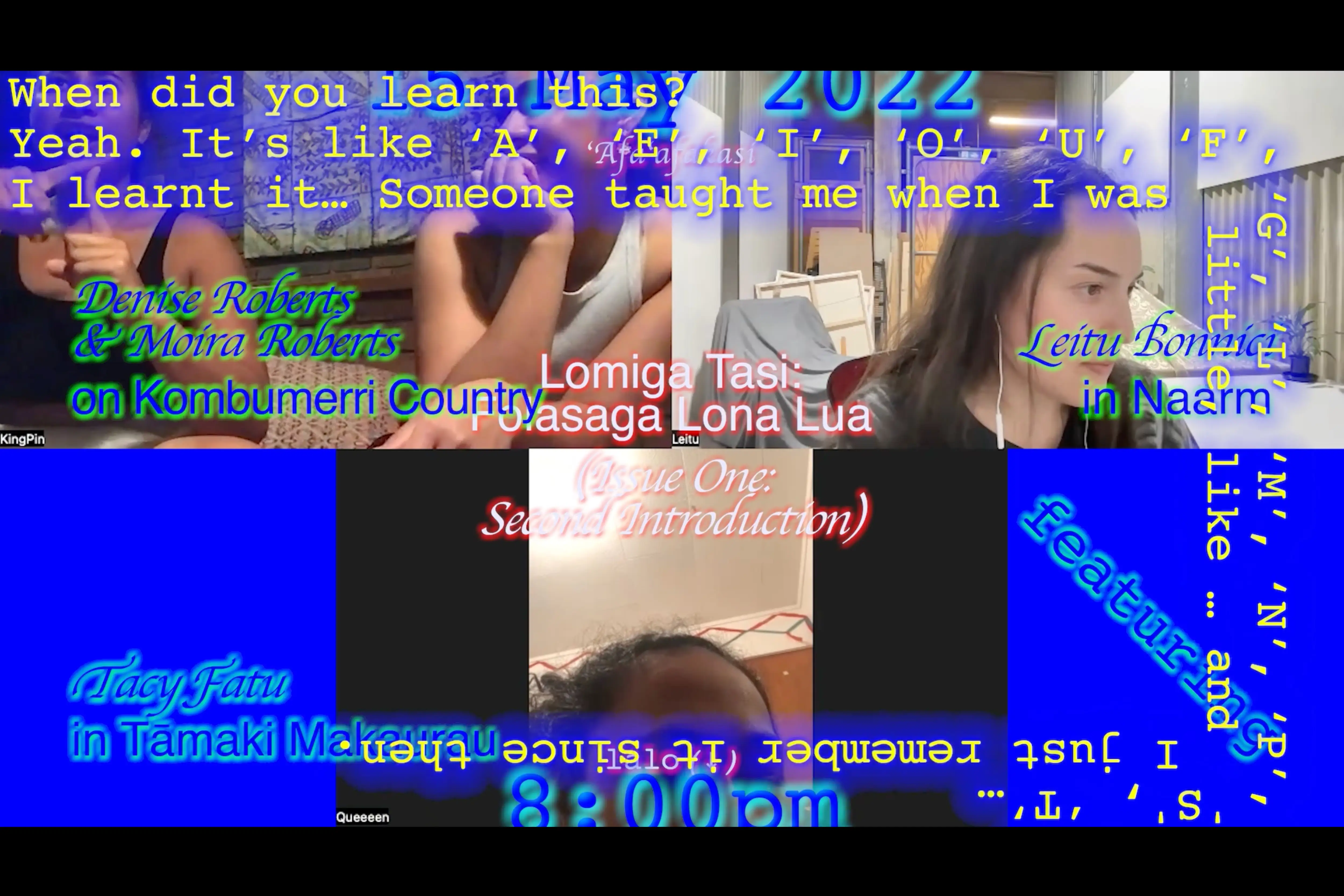

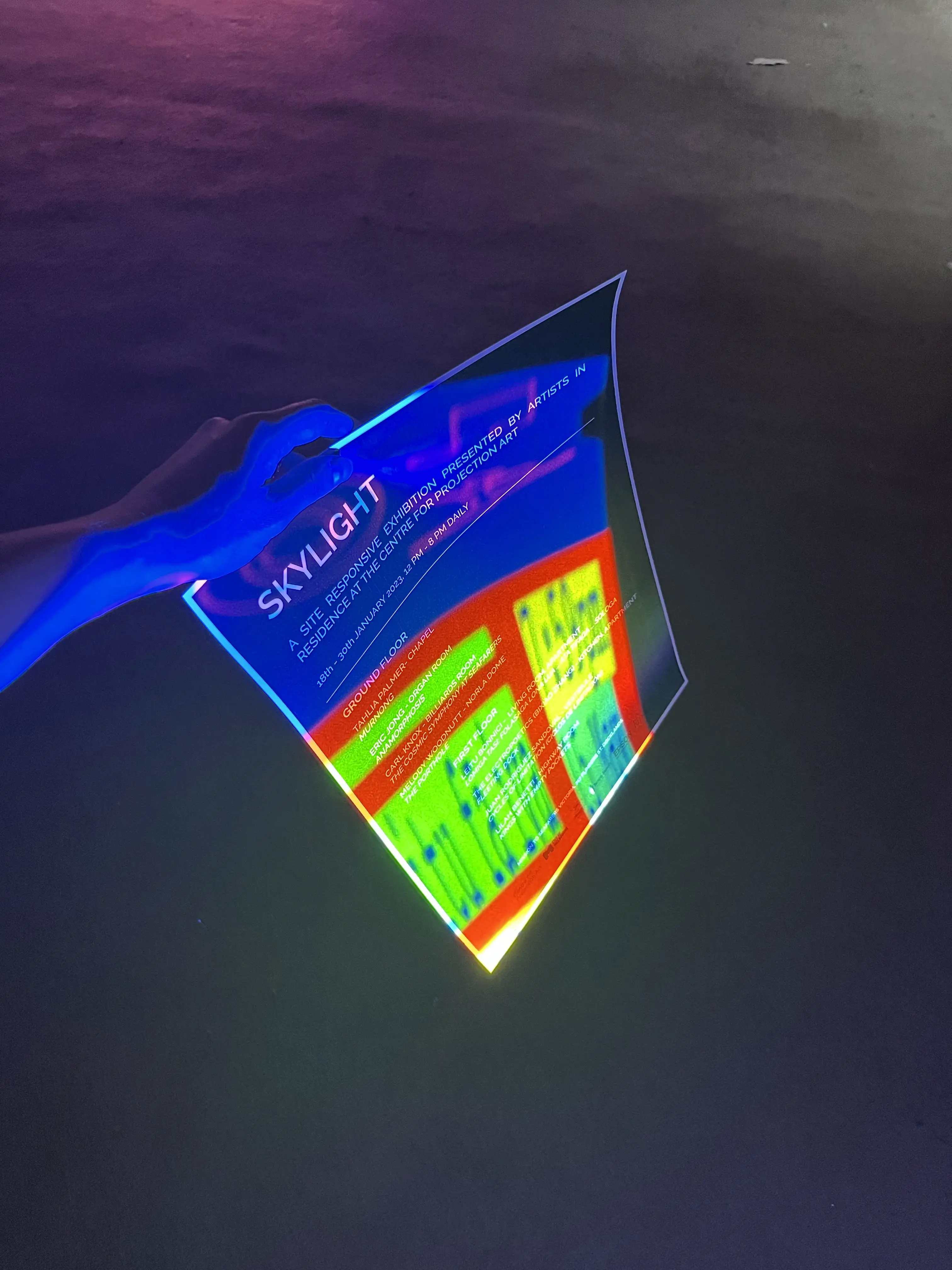

The files for the two projectors were updated just before the exhibition ‘Skylight’ opened on 20 January. The exhibition ran 20–30 January. The files were re-adjusted on 26 January. The closing event was on 27 January.

¶

A lot was learnt quickly during the masterclass and the tight turn around time for the exhibition. The opportunity was taken to play with the presentation of content for an exhibition in development showing in September.

What worked:

- using ‘outtake’ footage from the zoom calls to illustrate relationships, mishaps and add humour

- casual tone to explore complex issues

- including singing and dancing

- variety of elements (i.e. zoom footage, phone footage, captions, screenrecordings, illustrations, time stamps)

- multiple narratives overlapping at the same time

- bright and defined sections of colour

- overtaking spaces and site specificity

What could be worked on:

- the selection of footage

- more purposeful use of sound

- finding ways to add depth to layers on a flat wall

Next steps:

- contact gallery

- exhibition plan

- look at funding options

- sort and edit Zoom footage

¶

On 30 January an accidental meeting occured with Centre of Projection Art CEO, Priya Namana, when early for another meeting at the Centre of Projection Art space.

Off the back of a brief conversation the previous day with West Space curator, Sebastian Henry-Jones, an idea was mentioned of work involving projection that could take place at Collingwood Yards during Sāmoan Language Week. Priya gave a lot of advice, suggested writing a proposal and to start planning the project as soon as possible.

¶

Also on 30 January was a casual meeting and brainstorming of ideas with Jamali Bowden, after first meeting at the Blak Dot Gallery closing event and discovering a mutual interest in typography, projection and collaboration.

Time was spent becoming familiar with each other's work, and discussing things such as audience participation, live mapping with projection and other experimental approaches to performance. Also spoken about was labour and class society in relation to art, as well as division of labour including extremes in terms of roles and songs that accompany particular tasks. Jamali gave the example of different songs sung for fast and slow rope pulling, and noted how rhymes, alliteration and choruses are used to remember tasks.

¶

The first meeting with mentor Abeera Kamran occured via Zoom on 1 February. It included introductions, talks about some of Abeera's previous working including mapmaking, website collaboration and working with Urdu in relation to typography.

Mapmaking:

- maps that reflect the way inhabitants experienced a place instead of imposed narratives

- colonial version of mapmaking focuses on boundaries, spatial fields that are locked in, maps are flattened

- different ways people have moved across cities, land displacement, ecologies

- multiple creators of maps, inhabitants submitting their own videos to document their own changing landscape

- bring your own body when gathering information, politically charged spaces

Examples of projects Abeera has worked on:

- http://telas.parts/

- http://www.exhaustedgeographies.com/

Typography:

- working with scripts rather than Latin characters

- the difficulties of typesetting a stacked script (inconsistent baseline) with so many letter form changes

- Urdu script does not adapt well to Western print and web frameworks

¶

On 3 February was an outing to ACMI to see ‘How I See It: Blak Art and Film’ with fellow residents Tahlia Palmer and Lilah Benetti.

¶

The first week of February was spent putting together applications and proposals for forthcoming work and potential projects.

Quarry Pedagogies:

- attend the inaugural Quarry Pedagogies Camp 12–17 February

- ongoing rehabilitation as a creative process run by These Are The Projects We Do Together

- participants have been asked to form projects that explore alternate modes of rehabilitation alongside other camp activities that include collective care of the land, presentations and workshops

- idea to look at a digital, non-traditional form of ʻie tōga to experiment with how the incorporation of Sāmoan knowledge can shape new structures of archive and publication

- exchanged during special events to show respect and strengthen relationships

- woven with words, imagery and sound but replicate aspects of the traditional process (intertwining material with physical exertion and care in a collective setting, over a period of time)

Sāmoan Language Week:

- an evening of communal karaoke in gagana Sāmoa (Sāmoan language) to celebrate Vaiaso o le Gagana Sāmoa (Sāmoan Language Week)

- coincide with the show ‘Lomiga Lua: i Luga ‘o le Moana’ in the West Space Window and extend celebrations

- activation of public spaces in Collingwood Yards through projection

- accompanying publication

- options for collaborations or curation

- connecting to community, potentially bringing in food, performance, music etc.

¶

On 8 February was the first of ten Siva Sāmoa lessons with Le Masiofo Siva Academy. The focus was on harmonising in groups through song.

Number patterns:

- 1

- 1-2-1

- 1-2-3-2-1

- 1-2-3-4-3-2-1

- 1-2-3-4-5-4-3-2-1

- 1-2-3-4-5-6-5-4-3-2-1

- 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

- 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1

- 8

- 8-7-8

- 8-7-6-7-8

- 8-7-6-5-6-7-8

- 8-7-6-5-4-5-6-7-8

- 8-7-6-5-4-3-4-5-6-7-8

- 8-7-6-5-4-3-2-3-4-5-6-7-8

- 8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8

Savalivali song:

- savalivali means go for a walk

- tele tautala means too much talk

- ‘alofa ‘ia te ‘oe means I love you

- take it easy, faifai lemu

- e ua malie o

- ave i le malo

- e le faia so’u loto

- a e tu’u lou finagalo

¶

On 8 February was the second catch up with mentor, Abeera Kamran. The session went for two hours and was structured to focus on design in the first half (dissection the publication and installation feedback), and typography in the second (a presentation of Abeera's masters research and laying foundations for typographic research).

‘Skylight’ installation feedback:

- what worked: playful approach, publication as unbound, videos serve as entry points, portrait videos feel more intimate than landscape (landscape feels more formal), portrait videos also subtly echo, doors section works the best (intentional ayering and close together)

- how it felt in the world: regular videos of life being lived, extraordinary not needed

- what could be done differently: play more with composition

- what didn't work: connections to other iterations of volume accross mediums so the ghost of the different ‘sections’ are present (give someone who sees one section a chance to be exposed to other parts), composition of the main wall felt scattered and could be more intentional (a strategy is to impose one limitation per drawing sketch to see how compositions respond to each limitation), prefer compositional tightness to the scattering and absence of composition in main frame does disservice to concep (improve through a greater intent behind scattering)

Dissecting ‘the publication’:

- the authority of ‘the written word’ versus ‘the voice’ in different cultures

- percieved orientation (for example books not often rotated as read)

- the hegemony of the margin

- margins always thought of as space (not, for example, block elements like thick lines)

- Western stoic attitude, pleasure is suspicious, space for experimentation thought as for art and poetry or only for ‘special occasions’, publications with mundain uses are never elevated

- the one logic that you have to subscribe to, otherwise not considered practical

Reflection on current practice:

- single volume spanning multiple mediums, publication as unbound space, concept of publication is fluid and constantly changing

- take a step back (big ideas have already been though of) zoom in and think about scope of each work, think through strengths and weaknesses

- make pairings, think of the way mediums have more chemistry with other mediums

Typography and culture:

- interogate biases

- ask what is important culturally and why

- Western typography is characterised based on visuals (what are other ways to categorise, for example phonetically)

- how to deal with English ‘loan’ words

- typeface informs language which informs identity which informs culture etc.

- instances where latin characters have been imposed on cultures that have no connections

- changes to typography to make it more amenable to printing

Typographic research pointers:

- start documenting facts that are available to you

- history building, try to put pieces together

- put together a timeline (for example when was the first print document, when was the first digital document)

- example of a First Nations typographic project: https://www.typotheque.com/blog/north_american_syllabics_fonts

¶

On 9 February was a grant workshop session with Auspicious Arts at the Centre for Projection Art space.

Auspicious Arts:

- main concern is approving the budget

- sometimes artists work with Auspicious Arts because employing other people

- get in contact at least 10 days before the deadline

- they manage budget, superannuation

- makes doing tax a lot easier

- Auspicious Arts take legal responsibility for projects and deal with contracts

- no project too small, open door policy on art form, scale etc.

- predominately metropolitan artists, some regional and interstate

First step – Research:

- read the guidelines early on, highlight important parts

- find out if you are eligible

Second step – Strategy and Planning:

- build in contingency time, aim to submit a couple of days before

- people not often get top amount of funding

- hard to get first one on the board, get a smaller grant and leverage it, money attracts money, break funding down into stages increases chances of success

- get a sense of where you fit

Third step – Budget:

- recommend doing first

- work out whether project is viable, if not enough money to cover everything look where else can you apply for funding or how can you scale the project down

- think of as shopping list

- ball park is fine

- a detailed budget shows viability

Fourth step – Support Materials:

- investing time, energy and skill into amazing support materials, more important than rest of application as often what is looked at first

- get creative, an example of support material is to get someone to interview you about your work

- videos should be no more than two minutes, snappy and dynamic, only best bits, engage assessors

- overall practice or specific to project, depends on grant, could include both

- how can you make it easy for (support letters, give notice, give false deadline, give them dot points)

- make support letters reusable (don’t get them dated or mention specific grant but check to see if they’re with each application)

- can also get support letter from a partner in project when providing something in kind

Fifth step – Application:

- assessment criteria

- use grant speak (simple, effective, clarity, avoid art speak)

- confidence (for example I am doing this, we will do this, you give me this and this is what will happen, this is going to strongly impact the community by doing this…)

Sixth step – Outcome:

- generally have to wait three months

- outcome success rates are usually 10–25%

- always a good idea to ring up and get feedback

- outcome can depend on panel, projects you’re up against etc.

- if unsuccessful take the opportunity to refine the idea

Timeline:

- think of project as past, present, future

- funding application is present

- future is what happens to project after funded period, assessors want to know there will be life beyond funded period, looking for projects with a long life

- one page, three stages (past, present, future), dot point form, not super detailed

In-kind Support:

- usually includes your time, someone else’s time, equipment, venue hire

- some grants especially want artists to be paid (for example Creative Victoria no time in-kind, AusCo about 25% in-kind)

- mentor time (paid through other sources) in-kind

- accomodation, fuel, transport can be listed as in-kind

- can get support letter for in-kind equipment

Benefits:

- especially if applying for council funding

- what are the ripple benefits (for example benefits to other artists, people who get to see the work, people who relate to themes)

Contact:

- ring, meetings, ask to breakdown questions

- have clear questions and notes

- tell them about project, could ask what grant would be best

- ask if they will give you the full amount or a percentage (reflect answer in budget to make project viable)

- ask about support letters

Viability:

- budget making sense, does it tell the same story as you application

- artistic vision and impact most important, but budget may lift you above other applications

General Advice:

- sit on funding panels, get paid, artists at any level

- give to people in your industry and someone outside of it to read

- have statistics, government reports, other evidence etc. as evidence of claims

¶